Reviews

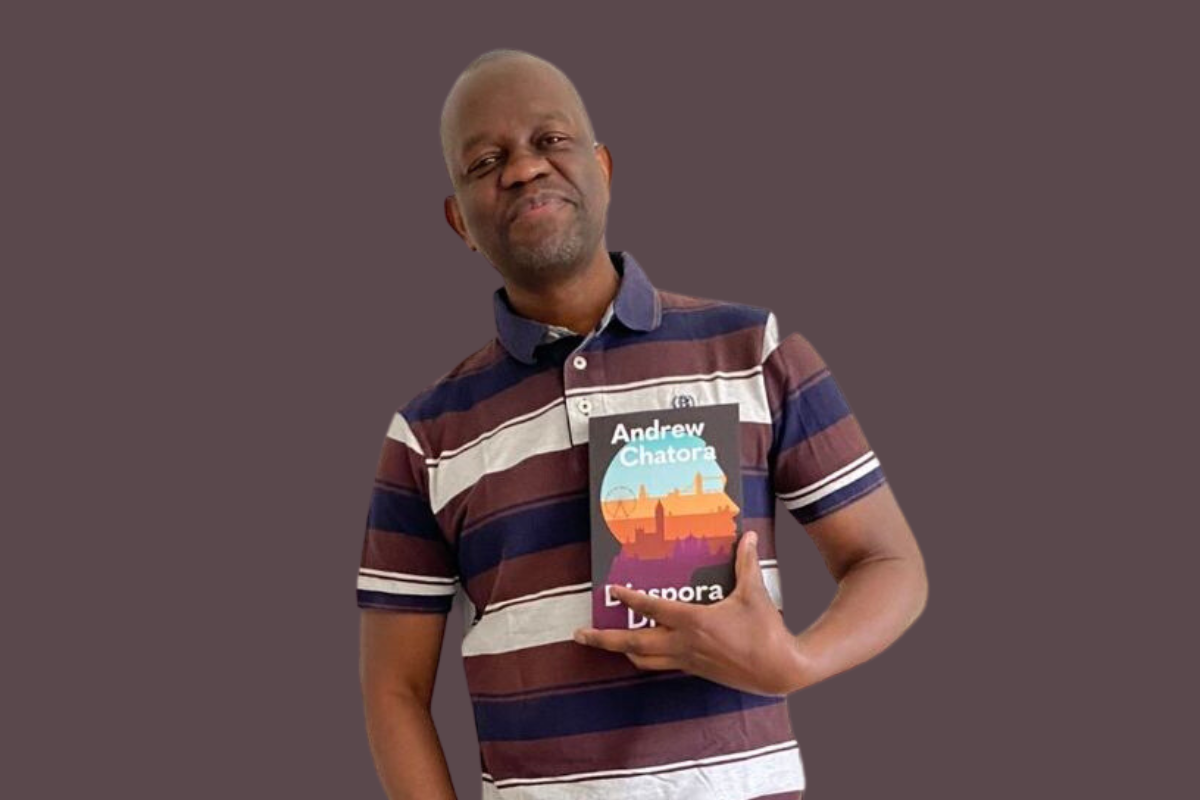

Navigating New Identities – A Review of Andrew Chatora’s “Diaspora Dreams”

Since Zimbabwe’s transition into a migratory nation, many Zimbabwean authors have dealt with the migrant question, Brian Chikwava’s Harare North and Sue Nyathi’s Gold Diggers being two stellar examples. Andrew Chatora’s debut novel Diaspora Dreams navigates new identities that Zimbabweans living in the diaspora are forced to assume and new challenges they must overcome to survive.

on

2002 was a year of economic upheaval that resulted in Zimbabweans leaving their country for greener pastures in the diaspora. While Australia, Canada and the United States of America were some destinations chosen by would-be economic refugees, most Zimbabwean emigrants settled in Johannesburg, South Africa – what would be coined Harare South and London, the United Kingdom which was subsequently dubbed Harare North. Therein lay the connotation that Zimbabwe and its people only existed in southern Africa as the Zimbabwean diaspora gained a greater cultural and economic significance. It is to this Harare North that the protagonist of Diaspora Dreams, Kundai Mafirakureva, arrives in the opening paragraph of Andrew Chatora’s debut novella:

I arrived in England on a freezing March morning circa, 2002, aboard a South African Airways flight. I felt nervous as I made the long walk to the immigration exit point. “Good luck,” a young white couple who had been sitting next to me on the eleven-hour flight from Johannesburg, South Africa, politely whispered in my ear, as I prepared to disembark from the plane. Perhaps, they had sussed me out; wet behind the ears, a newbie, out to trying my luck in entering England, for my fair share of what they term the American dream across the transatlantic in the United States.

Since Zimbabwe’s transition into a migratory nation, many Zimbabwean authors have dealt with the migrant question, Brian Chikwava’s Harare North and Sue Nyathi’s Gold Diggers being two stellar examples. Although our protagonist, Kundai first arrives in London (Harare North), ill-luck soon pushes him to Thames Valley where he must endure differing periods of good and bad fortune.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel, Americanah, one character, Obinze, remarks that British racism differs from American racism in that Americans have no qualms working with Africans, yet they are averse to living with them, while Brits will readily live with Africans but are averse to working with them. This characterisation is brought to the fore in Diaspora Dreams as Kundai’s white mistress is keen to take up with him but his colleagues are not always as welcoming.

In his first British job, Kundai works illegally as a valet in Aylesbury. As he is a foreigner with no work permit, his colleagues take advantage of this fact to make him do the grunt work and paying him an unfair wage, threatening to report him to immigration authorities if he complains. After getting a permanent visa and getting accreditation as a teacher, Kundai enters Britain’s public school system and although his position there is more formalised and secure, this is not the end of his woes.

While the racism and xenophobia of Kundai’s blue-collar colleagues in the valet service is vicious and blatant, the racism he encounters as a teacher in the public school system is nuanced and thus more sinister as it chips away at him slowly. A disheartening fact as it brings to mind Sidney Poitier’s stellar performance in James Clavell’s To Sir With Love. The 1967 film details the constant microaggressions a black teacher faces while teaching white children in 1960s Britain and highlights the restraint he must apply in being “the good black.”

The grand irony of the setting here is that the petty squabbles and bullying one expects from school children is rather enacted by the pedagogues and disciplinarians entrusted to shape the minds of the youth

Sadly, while Kundai’s students are more respectful in the 2000s, he still faces systemic racism enacted by his fellow colleagues and superiors. The grand irony of the setting here is that the petty squabbles and bullying one expects from school children is rather enacted by the pedagogues and disciplinarians entrusted to shape the minds of the youth. Chatora deftly uses the race and nationalities of Kundai’s colleagues as counterpoints to reinforce and highlight Kundai’s plight and the plight of other teachers of African descent, creating a sense of isolationism as African teachers are tacitly excluded by British teachers and often paid lower wages:

…for here I was, leading a highly successful Media department but without a financial acknowledgment of teaching and learning responsibility (TLR) to go with it, and in scenes reminiscent of my UPS1 threshold application at PRS, I had to approach the head; Simon Reece to rightfully ask what other middle managers were getting. After much haggling and arm-twisting Simon agreed to give me the lowest TLR on the scale! Such is the black man’s experience in English schools. I am not bitter, but I am clearly recounting my experiences for the over two decades I taught in English schools. It is only now, following the dreadful killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in the United States in 2020, that I feel brave to speak out against some injustices I experienced. As tragic as it is; George Floyd’s cataclysmic death has given me a voice.

Apart from the isolationism Kundai experiences in the work environment, his personal life is a suffocating series of messes that go from bad to worse with each passing chapter. The narrator, Kundai, believes in his Shona values and seeks to uphold them especially while he is in the diaspora as this culture is his only real link to his motherland. In all his decision making and his worldview, Kundai refers to his people, his hunhu (ethos), and his mutupo (totem) characteristics.

Unfortunately, his wife Kay chooses to rather adopt Western individualism and falls prey to materialism, manipulating the court system to her own advantages. Thus, while Kundai and Kay dreamed of the UK as the ‘greener pastries” the change in environment splinters their relationship further. Kundai and Kay’s relationship is a point of departure to look closely at globalisation and the death of the traditional Shona wife. While Kay was in Africa, in a society that was more patriarchal and communal, she and Kundai had fewer marital problems, but when she forges a new individualistic identity for herself in the West, things fall apart. Furthermore, in the traditional Shona household, men are providers and the heads of the families but with the Mafirakureva’s changing fortunes and reversal of roles in the UK, Kundai finds himself emasculated by his wife:

The relationship was lopsided against me. Perhaps, I resented Kay for earning more money than I; quite a huge reversal of fortunes from when we worked in Zimbabwe. Inwardly, I felt like Kay was challenging my masculinity now that her salary was way ahead of mine, and she tried to exercise her newfound dominance in the marriage by sometimes making unilateral decisions without evening asking me my input on matters which also impacted on me. I felt muted in the marriage as if my voice did not matter.

Kundai fails to grasp this new identity resulting in the decline of their marriage. This splinter is further explained in Kundai’s identity as a member of the Gwai (sheep) clan who value humility and as such can neither understand nor entertain Kay’s abrasive behaviour.

Similar themes are echoed in other Zimbabwean novels on the topic of migration, Tendai Huchu’s 2014 novel, The Maestro, the Magistrate, and the Mathematician zooms in on the dislocation experienced by three Zimbabwean expatriates residing in Scotland while Chikwava’s Harare North is an examination of London’s seedier underbelly that is preoccupied with the deterioration of immigrants’ loss of social fabric. Such circumstances tend to have cumulative effects on one’s mental health as shown in Chatora’s Diaspora Dreams. While Kundai acknowledges that living in the UK has damaged his relationships and mental health, his status as an economic refugee does not allow him the privilege of permanently returning to Zimbabwe. This aspect of immigrant life is captured eloquently in Rodolfo Gonzalez’ poem, “I am Joaquin”:

My fathers

Have lost the economic battle

And won the struggle for cultural survival

And now! I must choose between the paradox of victory of the spirit despite physical hunger,

Or to exist in the grasp of American social neurosis,

Sterilization of the soul and a full stomach.

ADVERTISEMENT

The added pressures of Kundai’s immediate and distant relatives increase this pressure as they assume all Zimbabweans in the diaspora are wealthy and thus apply to him for money on a regular basis:

Over the years, it has increasingly been difficult to pinpoint one single reason to why our union soured so quickly. There are moments when I think I get it, but even now I am not so sure anymore. I know the overbearing family demands and expectations from Zimbabwe also ended up taking their toll on the marriage, but to what extend did both of us play a part in the dissolution?

Such overtures are also discussed in NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names, which tackles the lives of Zimbabwean immigrants living in the United States of America.

There is more to the narrative than just Kundai’s cataclysmic relationships with women as the author deftly paints the touching relationship both Kundai’s children have with their father. These outings are juxtaposed against the protracted custody battles that Kundai and Kay engage in, causing the reader to have sympathy for second generation immigrant children, who often bear the brunt of deteriorating marriages in the diaspora, and thus Kundai ends the chapter on a poignant note:

”There was no need for all this, I didn’t need to prove to anyone that I love my children …my conscience is my master.”

Thus, Kundai’s relationship with his children humanises him by showing him as a fully fleshed human being with different interpersonal relationships and sheds a brighter light on the lives of migrant families.

Apart from the timely themes that Diaspora Dreams touches on, Chatora’s minimalistic/simplistic writing style is reminiscent of Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen (In the Ditch)

Apart from the timely themes that Diaspora Dreams touches on, Chatora’s minimalistic/simplistic writing style is reminiscent of Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen (In the Ditch) and the protagonist, Kundai, takes on the persona of the everyman, allowing the reader to cheer for his success and balk at his failures and setbacks. As more and more Zimbabweans leave the southern African nation for greener pastures, stories such as Diaspora Dreams will increasingly become more relevant and pertinent to the Zimbabwean canon as they highlight new identities that Zimbabweans living in the diaspora are forced to assume and new challenges they must overcome to survive.